The Thematic approach

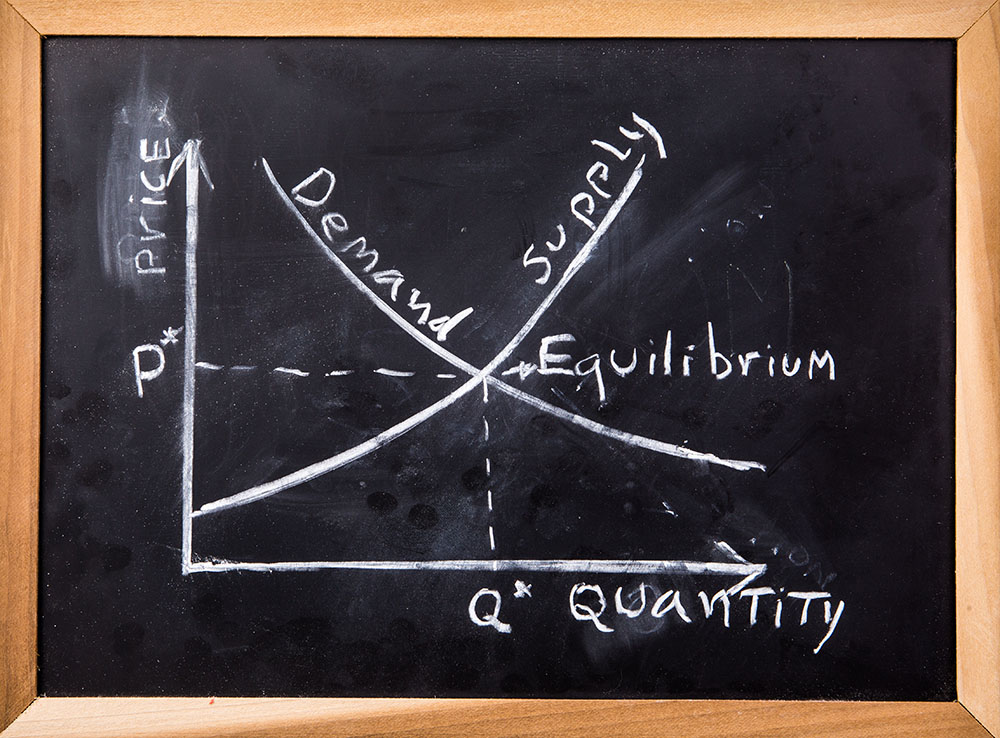

The Thematic approach to analysis recognizes that most trends in the global political economy and markets are driven by long-lived natural, evolved phenomena – or Themes – whose effects, like the speed or position of subatomic particles, may change when observed. Themes have a life cycle, arising in the background without notice, like Adam Smith’s “invisible hand”, before their effects are observed by early identifiers and later enter the consensus’ consciousness with a “name” (e.g. hyperglobalization, or Bretton Woods II).

Early identification and understanding of emergent themes enables one to make better sense the global political economy, improving market forecasts and putting you ahead of the consensus (see Successes).

Themes are different from narratives, though they may overlap at times. Understanding the difference is crucial. Narratives are powerful ad hoc stories created to sell products (e.g. BRICS) or to explain phenomena that markets struggle to understand (e.g. secular stagnation or new normal). Themes are the fundamental phenomena underlying the things markets can’t explain. When narratives align with Themes, they powerfully amplify their effects on market prices. But when they are at odds, narratives can lead to fundamental divergence that ultimately resolves in dislocating volatility (e.g. in 2022 when bond markets’ secular stagnation narrative met the fundamental reality of Localization).

The following Themes have driven the global political economy for the last three decades. The ongoing Themes are those that are most important to the current outlook. But understanding past Themes, often with lingering effects, is crucial to understanding how we got here and the effects current Themes generate.

Current and ongoing themes:

Global bifurcation

The US and China split the world, technologically, economically & financially

After three decades of integration, the global economy is again splitting into two spheres for technology, payments, trade, and finance. Driven by national security concerns and mutual distrust, the two largest, most powerful nations and centers of technological development, China and the United States, are dividing the world between them. Bifurcation of technological platforms – e.g. 5G systems – already is well advanced. US abuse of financial sanctions is pushing China and its satellites out of the US payments system, while US trade agreements increasingly impose disadvantageous terms on China (e.g. USMCA and the US agreement with the UK). Contrary to consensus views, because the members of each camp remain fluid, Global bifurcation is more likely to manifest as Localization than so-called “near shoring.”

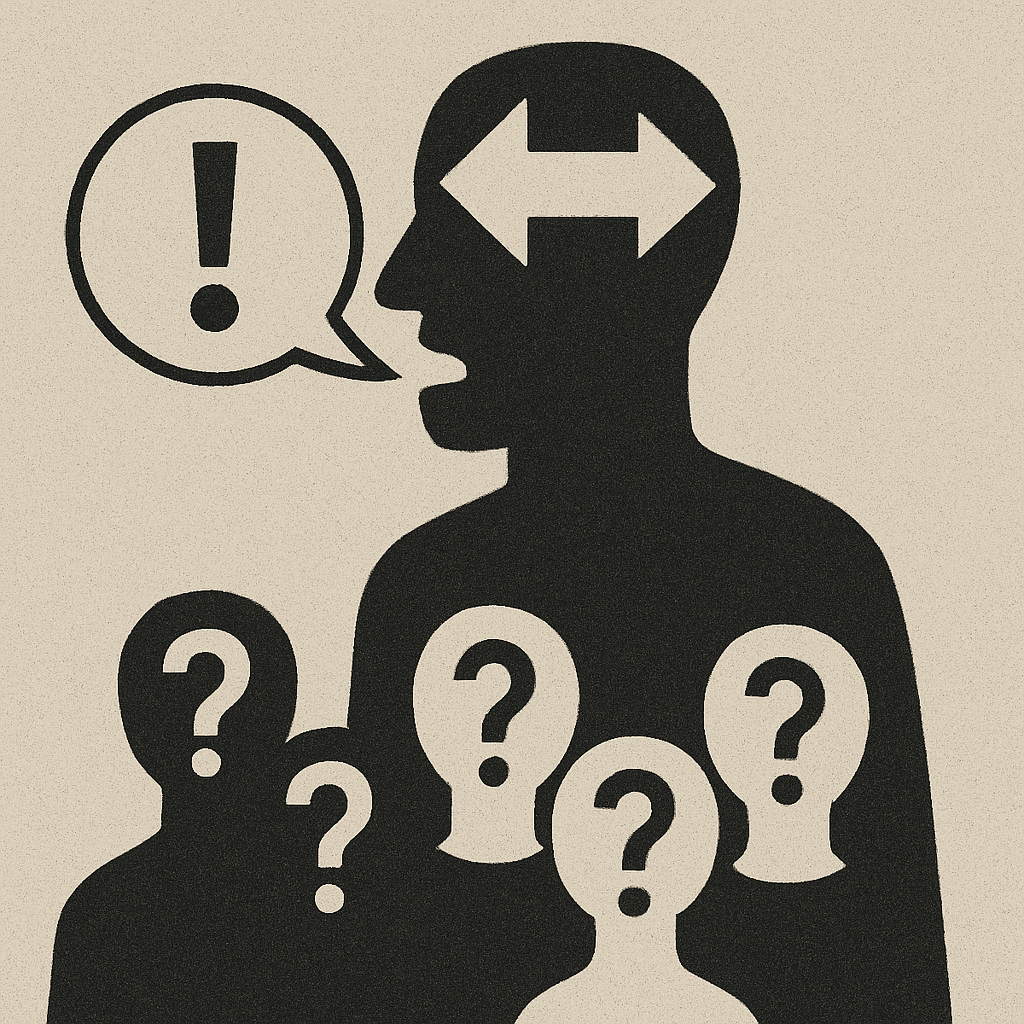

Cultural dissonance

Western elites' internal contradictions risk greater political and economic fissures

Western elites increasingly suffer from self-contradictory beliefs that are being exposed by Global entropy and the Politics of Rage. In foreign policy, they champion “universal” values — such as tolerance and human rights — yet impose them through economic sanctions and military force, without acknowledging the inherent hypocrisy. At home, elites demand that native citizens embrace tolerance towards immigrant populations, while ignoring some immigrants’ intolerance toward the host society or other immigrant groups. Democracy is upheld as a sacred value, even as the less-educated majority is treated with contempt and viewed as needing rule by experts rather than self-governance. Cultural dissonance erodes public trust, fueling social fragmentation, and weakening the civic foundations (“social capital”) that support both liberal democracy and economic resilience.

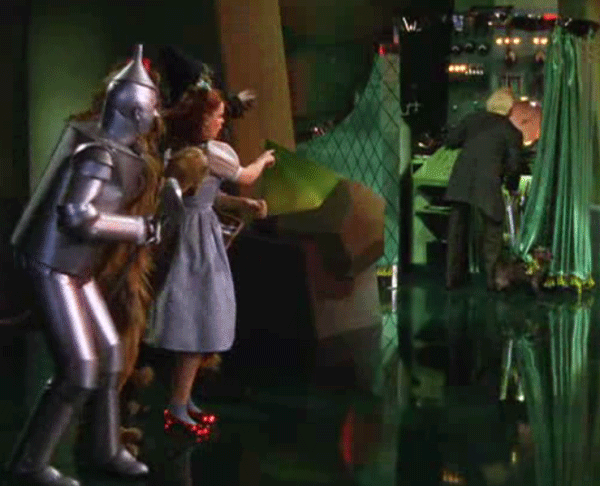

Illusory omnipotence

Reality tests markets' faith in Western institutional omnipotence

The façade of stability created by decades of Pax Americana and Apex neoliberalism created a false sense in markets – and most dangerously in policymakers themselves – of Western policymaking omnipotence. Yet the cracks are beginning to show. Both inflation and interest rates have not behaved as expected. UN Charter Article 2(4) has been tossed in the rubbish bin by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. China builds new islands fortresses in the Exclusive Economic Zones of other nations. The Houthis hold off the US and other navies in terrorizing global shipping. Market pricing embeds a strong belief that policymakers can and will solve most dislocations, despite increasing evidence that may prove horribly wrong.

Global entropy

Manifest and growing disorder

By ignoring the endogeneity of complex systems and Rodrick’s globalization trilemma – that democracy, national self-determination, and economic globalization cannot enduringly coexist – Apex neoliberalism sowed the seeds of its own demise, leading to today’s manifest…

Missingflation

Economists don’t understand inflation

What are economists missing about inflation? In the two decades before Covid, market analysts, academic economists and central banks consistently overforecast inflation; in the last two years they have persistently underforecast it. Enduring one-way errors are not…

Believing is being

Self-fulfilling beliefs are real

Beliefs drive everything from asset bubbles, to debt dynamics, to crypto currencies’ values, to inflation and hyperinflations (probably Missingflation, too). Good economists understand this but often omit beliefs from models to simplify because of the difficulty in…

Localization

Automation is unwinding globalisation

Human economic history largely has been a story of increasing economic globalization, yet the last decade has witnessed the reverse: localization of production. The trend began before trade wars and is likely to continue well after Covid and the Politics of Rage…

Complexity cascades

Complex systems fail unpredictably

Human societies, nation states and (especially) economies are examples of complex systems. Complex systems always operate in “broken” mode and ironically are more structurally stable when they have lots of small failures. But when they are subjected to massive…

Uncertainty

Not all risks can be quantified

All risks are not the same. Some are quantifiable, like the chance of being dealt an ace in a game of cards. Others are not but can be subjectively guessed, like the chance you leave a casino a winner. Then there is uncertainty, the most dangerous of all risks because it..

Politics of Rage

The proletariat want their franchise back

Four decades ago, globalization and increasing economic returns to intellectual capital opened a fissure between elites and everyone else, especially in more developed economies. The economic and political consequences of Apex neoliberalism widened this fissure into a…

Past themes with lingering consequences:

$Bloc/Chinese co-prosperity sphere

FX herding cures “fear of floating”

The “co-prosperity sphere” of bloc managed exchange rates centered around Chinese trade and the US financial system, alternatively known as Bretton Woods II or Chimerica, dramatically reoriented global supply chains, supported emerging markets’ financial…

Mercantilism (with Chinese Characteristics)

State capitalism’s unintended costs

China’s 1994-2012 “miracle” that lifted nearly a billion people out of poverty and its current growth problems both originate in its extreme application of the mercantilist “Asian growth model” originated by Japan and later copied by Asia’s “Tigers”. A combination…

Apex neoliberalism

Liberal capital democracy’s pyrrhic victory

Rapid global growth, particularly in the less developed world, “hyperglobalized” production and the growth of inter-governmental coordination derive substantively from the triumph of neoliberalism that followed the collapse of its ideological competitors with…